- japanese

- english

Statistic Study about Japanese Patent Infringement Cases

[Japan] - Current Situation of Infringements under the Doctrine of Equivalents in Japan -

1. Five Requirements for Determination of Equivalence

In the judgment on the "Infinite Sliding Spline Shaft Bearing" Case [Heisei 6 (1994) (O) No. 1083] delivered on February 24, 1998, the Supreme Court of Japan provided the conditions for applying the doctrine of equivalents and guidelines for equivalency. On the ground that a portion of the guidelines was ignored, the Court quashed the original judgment and remanded the case to the Tokyo High Court. Since then this judgment has been exploited as the authority for finding or denying an infringement under the doctrine of equivalents in Japan. The following five requirements must be all satisfied for asserting the doctrine of equivalents:

1) The part different from the product, etc. in question in the structure described in the scope of the patent claim is not an essential part of the patented invention (non-essential part);

2) The replacement of the different part with the corresponding part in the product, etc. in question may achieve the object of the patented invention and has identical function and effect (possibility of substitution);

3) A person skilled in the art may easily arrive at an idea to replace the above mentioned different part at the time of manufacturing of the product, etc. in question (ease of substitution);

4) The product in question is not identical with known prior art nor is it easily conceivable based on the known prior art by a person skilled in the art at the time of filing of the relevant application (non-prior art); and

5) There are no special circumstances for the product, etc. in question to be deliberately removed from the scope of the patent claim in application procedures of the subject patented invention (non-conscious exclusion)

2. Recent Status of Confirmation of Infringements of Patent Rights or Utility Model Rights

The author classified the judgments on cases of patent (including utility model) infringements (82 cases in total) delivered by 4 courts, the Tokyo District Court, the Osaka District Court, the Tokyo High Court (later, the Intellectual Property Court), and the Osaka High Court (excluding the decisions of other courts) since the "Infinite Sliding Spline Shaft Bearing" Case through 2009 into: a) judgments confirming the infringement of a patent right; and b) judgments confirming the noninfringement of a patent right. The author further categorized the judgments a) in terms of literal infringements and infringements under the doctrine of equivalents, and also summarized the judgments b) on a "Requirement" basis for the noninfringement of the right under the doctrine of equivalents.

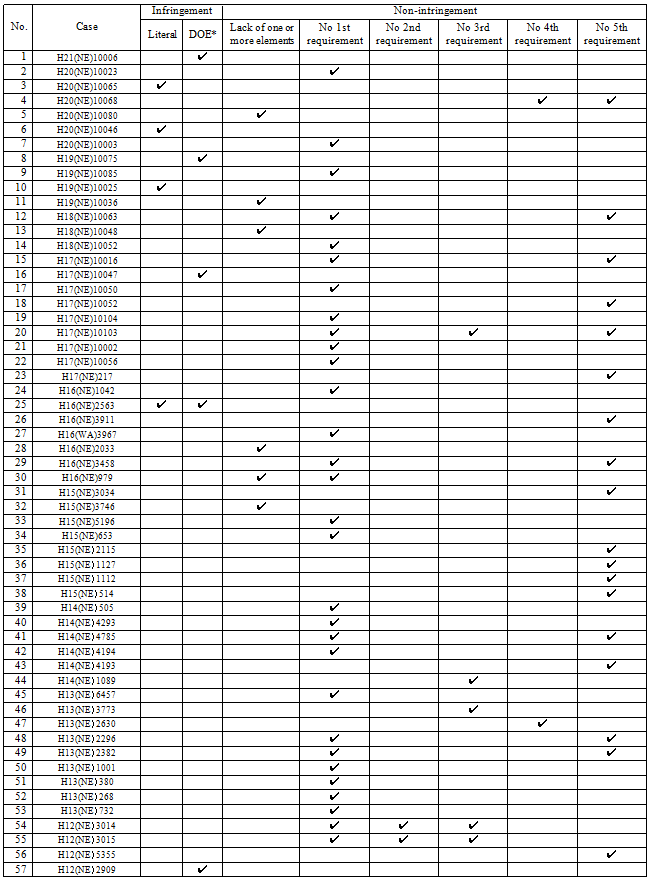

The results are shown in Table 1.

1) Of the 82 judgments, only 14 (about 17%) confirmed the infringement of a patent right, whereas the remaining 68 judgments (about 83%) confirmed the noninfringement of a patent right.

2) Of these 14 judgments confirming the infringement, 7 found a literal infringement, whereas the remaining 7 judgments found an infringement under the doctrine of equivalents, one of which was however denied later by a retrial.

3) Of the 68 judgments confirming the noninfringement, 7 were based on the complete lack of one or more of the elements indispensable for the structure described in the scope of the patent claim, whereas 61 were based on the absence of one or more of the aforementioned five requirements.

4) The largest proportion of the 61 judgments based on the absence of one or more of the aforementioned five requirements was made on the ground that the part different from the article A in the patented invention is not an essential part of the patented invention (Requirement 1). These judgments formed because of not meeting Requirement 1 occupied 43 out of the 61 judgments (about 70%). The second common ground was that there are no special circumstances for the accused infringer to be deliberately removed from the scope of the patent claim (Requirement 5). These judgments formed because of not meeting Requirement 5 occupied 25 out of the 61 judgments (about 41%), followed by 8 judgments (about 13%) formed because of not meeting Requirement 3 (ease of substitution), 5 judgments (about 8%) formed because of not meeting Requirement 2 (possibility of substitution), and 2 judgments (about 3%) formed because of not meeting Requirement 4 (non-prior art).

3. Discussion

Notice that only a very small percentage (about 17%) of the judgments confirmed the infringement of a patent right. This number certainly reduces an incentive for the owners of patents or utility models to file patent infringement lawsuits.

It is also to be noted that as few as 7 judgments were in favor of plaintiffs' claims of infringements under the doctrine of equivalents, whereas as many as 68 judgments (also including the 7 decisions stating the lack of one or more of the indispensable elements) were against them. In the event of any litigation regarding a patent infringement, the doctrine of equivalents is applied to judicial decision in the absence of literal infringements. Once courts found no literal infringement, they may hesitate to admit an infringement under the doctrine of equivalents and often end up in rejecting the patentee's infringement claim.

What are the hurdles for establishing an infringement under the doctrine of equivalents? As seen from the results given in Table 1 and also in the foregoing paragraph 2, the non-essential part (Requirement 1) and the non-conscious exclusion (Requirement 5) are the major obstacles.

The non-essential part (Requirement 1) is unique to Japan, and this kind of requirement for the determination of equivalence is not found in the USA, Germany, China, or anywhere else. Under the concept of the non-essential part (Requirement 1), a so-called "core" (essential part) in the constitution of the patented invention is picked out on the basis of the descriptions of Problem(s) to be Solved by the Invention, Means for Solving the Problems(s), Operation and Advantage(s) of the Invention without being bound by the words of the patent claim. According to the typical decisions on the infringement cases, if the accused infringer differs in the "core" from the patented invention then it does not meet Requirement 1 (non-essential part) and is eventually regarded as not violating the doctrine.

In another case, Requirement 5 (non-conscious exclusion) may conflict with the doctrine of equivalents, even if Requirement 1 (non-essential part) can be satisfied. Requirement 5 (non-conscious exclusion) is often judged as being not met from the descriptions of amendments and/or written opinions submitted in response to the notice of reasons for rejection. In other words, action taken to differentiate the claimed invention from an invention disclosed in a reference cited by the examiner, etc. is partly responsible for interfering with the future establishment of an infringement under the doctrine of equivalents.

4. Answers to Problems Associated with Establishing Infringements under Doctrine of Equivalents

(1) For Meeting Requirement 1 (non-essential part)

The judges in their judgments used excerpts from the description of Problem(s) to be Solved by the Invention to examine Requirement 1 with almost no exceptions (this is partly because the defendants also cited such excerpts). Describing the objects in more detail tends to limit the essential part of the claimed invention more strictly. Some inventions may not be differentiated from the prior invention unless their specifications provide the detailed description of the objects. Quite a number of specifications, however, give the needlessly detailed description of the objects. The satisfaction of Requirement 1 requires the essential part of the claimed invention to be construed in the broadest sense. For these reasons, the description of the objects as simple as possible must help meet Requirement 1 (non-essential part).

(2) For Meeting Requirement 5 (non-conscious exclusion)

When responding to the notice of reasons for rejection or filing written requests for accelerated examination, for example, it is important to point out a distinction between the claimed invention and a cited invention as simply as possible without overexplaining. On the other hand, the distinction between the claimed invention and the cited invention may have to be defined for overcoming the reasons for rejection. Hence, assertion of the discrimination is something of a double-edged sword. The author recommends picking out an indispensable element of the claimed invention different from the cited invention, and merely stating that the element is not disclosed (or neither disclosed nor suggested, in the case of claiming the inventive step) in the cited invention, while not extracting the specific words defining the element. Also, function or effect that cannot be brought about by the cited invention should be indicated within the scope related to the objects described in the sption. This is a very common way to respond to the U.S. Office Actions. In patent infringement lawsuits, the conscious or non-conscious exclusion is determined on the basis of the extent to which the contexts of the limited literal language are removed through amendments made to the pending patent application or how narrowly the claimed invention is interpreted by the applicant in a written opinion in the absence of such amendments. The further extraction of certain words from the amended parts to differentiate the claimed invention from the cited invention would facilitate overcoming the reasons for rejection, but may be judged as removing the whole contexts of the certain words. For these reasons, the preparation of amendments and written opinions with due attention given to simplified expressions for differentiating the claimed invention from the cited invention must help meet Requirement 5 (non-conscious exclusion).